The exhibition was conceived to try to restore lustre to the somewhat tarnished reputation of a man who was the most gifted and extraordinary post-war Italian draughtsman and one of the greatest Italian engravers of the second half of the last century. Indeed, Vespignani became a draughtsman during the war, when his first drawings were displayed in the windows of the EIAR auditorium – the radio station of the time – to illustrate scheduled concerts as early as April 1943. In the following months, events would forever shape the personality of an artist who was already complete, mature and inimitable at only nineteen years of age. In July, the first bombing of Rome, immediately followed by the fall of Fascism, the armistice and the German occupation of Rome were Vespignani’s academy. The remains of San Lorenzo, impregnated with the stench of badly buried corpses amongst the rubble, his own house destroyed by the bombing of Portonaccio in March of the following year, were for the young artist like the forest of Fontainebleau for the first French Romantic landscape painters. His aesthetic was born from contemplation of the ruins of war, just as ancient ruins generated Piranesi’s genius. The comparison is not idle, as a contemporary biographer (L. Bianconi) recounts that the young Piranesi in Rome, drew day and night, but not Apollo and Laocoon, but ‘the most ramshackle cripples and hunchbacks that he saw during the day in Rome… legs stuck, arms broken, and skinny cudrioni… pieces of butcher’s meat, heads of swine and kid’. These were the author’s first exercises ‘Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’ Romani’, unfortunately lost, but those who saw them left written that such studies of repulsive objects were nevertheless executed ‘maravigliosamente bene’, marvellously well. In the same way, the destroyed houses, the abandoned wagons on the dead tracks, the desolate suburbs, the corpses pulled from heaps of rubble, the mangled dogs whose grieved ferocity prevents the mercy of a coup de grace, the discarded whores of Portonaccio, ruined as if by putrefaction by their age and trade, are Vespignani’s favourite subjects, terrible, but drawn ‘marvellously well’. So much so that they seem to be refined engravings: strokes finer than a hair, washed out by the brush as in an aquatint, intricate and insistent like the deepest bites of an etching, Vespignani’s mastery is unparalleled, especially because it does not show the slow evolution of an apprenticeship, but reveals itself suddenly, like a ripe fruit that has never been a flower: a few suggestions from the drawings of Franco Gentilini, a generation older; a shabby old book, stolen by chance from a cart, with reproductions of drawings by George Grosz. This was enough for Vespignani to unite the squalor of Sironi’s urban suburbs after the First World War with the bleakest horror of a Second World War that was still painfully struggling to arrive, with the Anglo-Americans pinned down at Anzio for a good five months.

While Rome was still occupied, it was Irene Brin and Gasparo dal Corso who discovered Vespignani, who happened by chance to be at the “Margherita” in Via Bissolati, a shop selling used books and a few works of art, to sell his drawings “for two lire”. This was followed by an exhibition in January of 1945 that was replicated in June, again at the “Margherita”, and the following year at the Obelisco, then a newly-established art gallery that the Brin-Dal Corso couple would transform into the most refined, active and cosmopolitan in Rome. Vespignani’s drawings literally sell like hot cakes, so much so that during the course of the exhibition itself, the artist is asked for more drawings to replace those sold. In addition to the Americans, of both old and new money, Irene Brin also recalls groups of high school students who would buy a single drawing in society for a handful of pennies from a hard-earned collection.

With Fascism, official art had collapsed like a house of cards, like certain avant-garde boots made of from pressed cardboard and dyed with black polish that Vespignani recalled ravaged by the first rain. Behind the scene was revealed a landscape of ruins that were those inhabited by Vespignani as a boy, following an affluent early childhood at the Esquiline, here he wandered as an evacuee, with fragile medical certificates in his pockets to avoid the danger of a round-up. It was this Academy of Italian Disaster in which the country was able to contemplate its own wounds and turn them into a poem that would amaze the world. The ‘Roman Mother killed by the Germans’, drawn by Vespignani, modelled and enamelled by Leoncillo, was actually from Calabria and was called Teresa Gullace, but the whole world knows her in the guise of Anna Magnani in Rossellini’s ‘Roma città aperta’, a commoner mowed down by a machine-gun fire while running behind a truck loaded with round-ups.

Vespignani was perhaps not the only one, but certainly the greatest interpreter of neo-realism in the figurative arts, and international fame also came for him, immortalised in pictures by Alfred Eisenstaed in 1947 – the photographer of the famous kiss in Times Square – he appeared on a page of Life after his works were bought by MoMA and he was invited to hold an exhibition in New York. As far as the American market was concerned, however, it was somewhat of ‘a flash in the pan’ – with Vespignani’s angry communist militancy soon closing the doors that had opened so genially, drawing Eisenhower as an armed skeleton strolling with De Gasperi and Scelba on a leash was not the best of references for obtaining a visa.

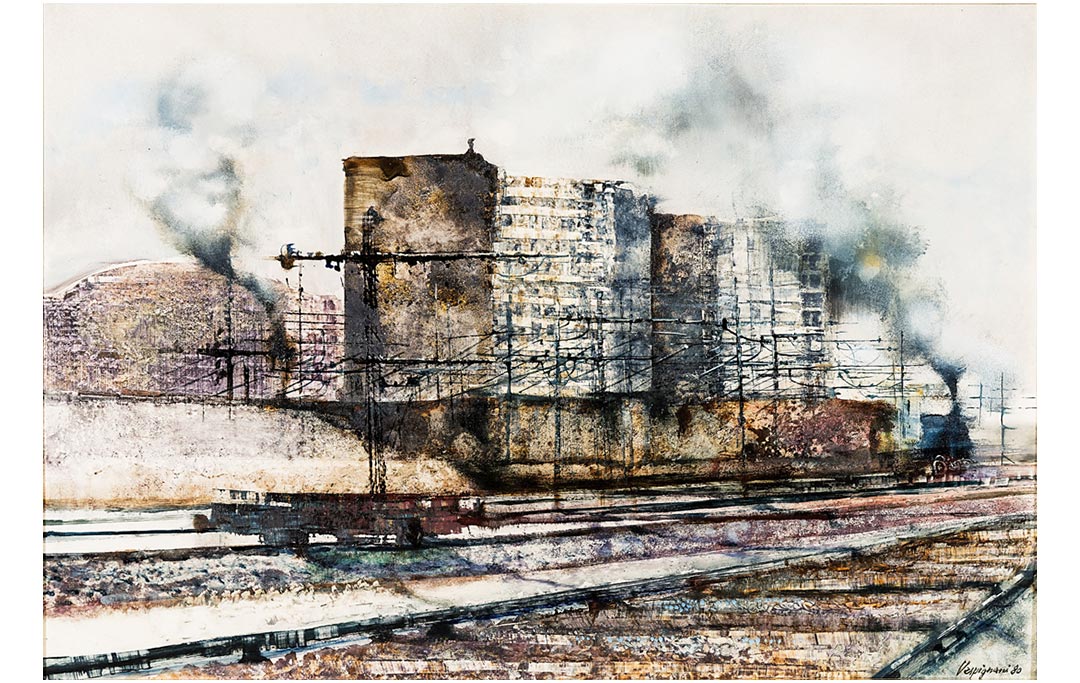

After all, even in peacetime Vespignani remained a ‘painter of ruins’; in the ‘boom’ years, the suburban blocks of flats growing like mushrooms in Italy’s affluence are drawn, painted and engraved with the same anguished signs with which he had described those destroyed by the bombs of the war: his whole time is recounted as one great cataclysm, with no solution of continuity between the ruin of the Second World War and the industrial development, urban growth and pollution they generated. The growth of prosperity for Vespignani always corresponds to the moral and material degradation of consumerism, which in the faces and bodies depicted degenerates into a sort of leprosy or decomposition, though always ‘marvellously well’ depicted.

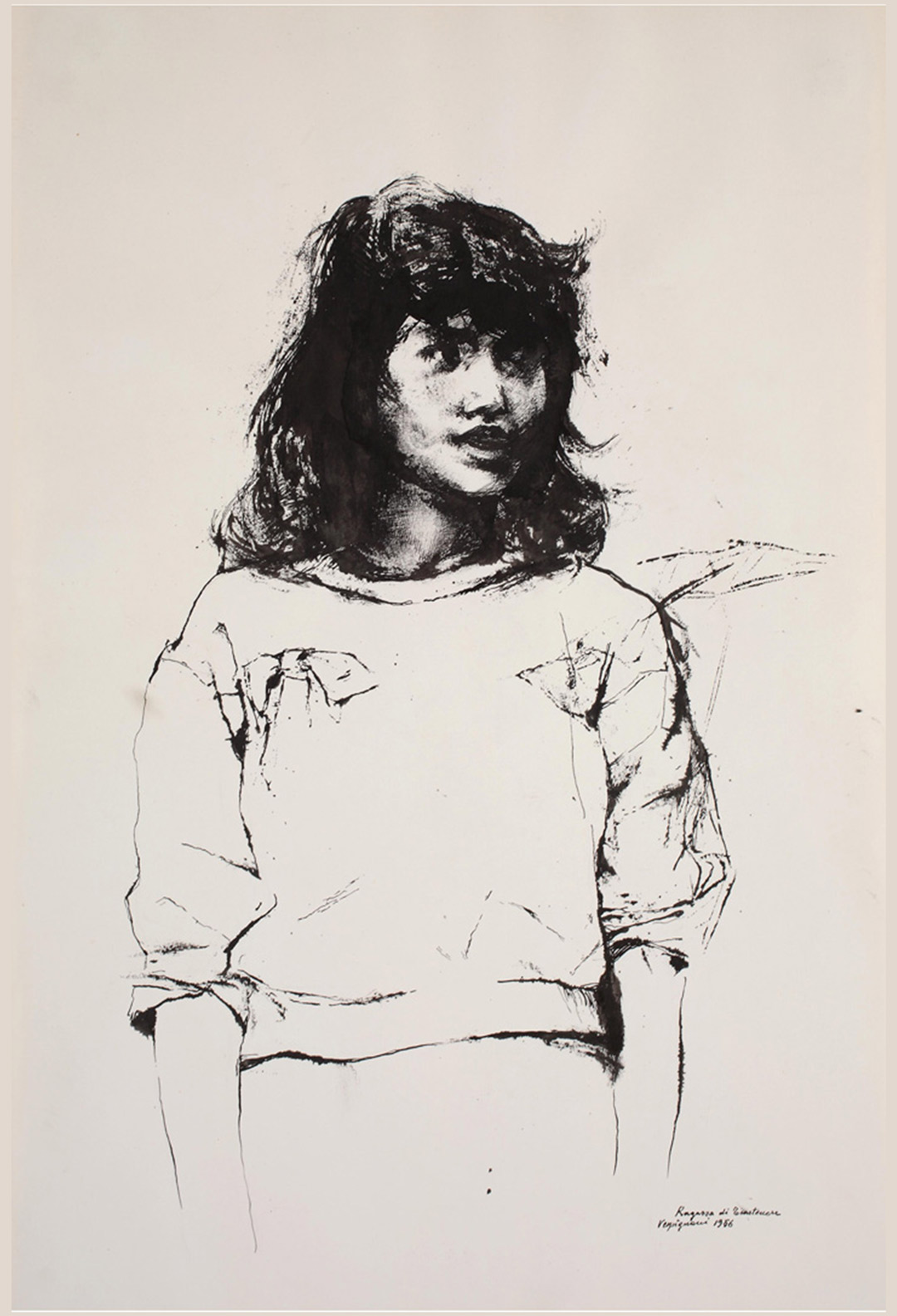

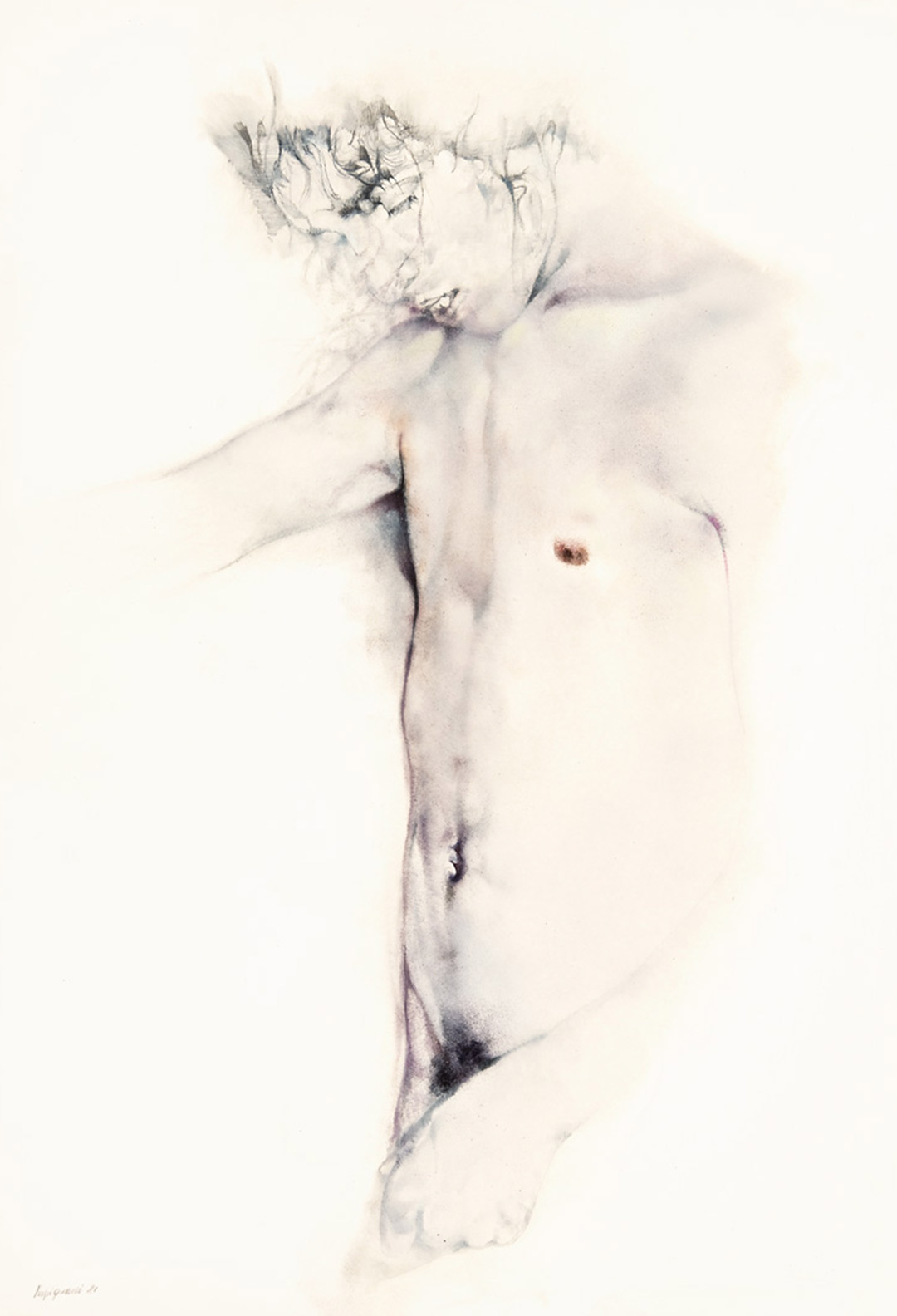

The road accidents, with crumpled metal sheets, shattered glass and bodies lying on the asphalt, are described as acts of war – of wealth against humanity – but reproduced with a refinement and expertise in detail, a sense of the sublime in the whole, that make Vespignani a modern ‘poet of ruins’ just as Piranesi was of ancient ones. Both are masters in representing decay, that of modernity on nature in Vespignani, that of nature on ancient monuments in Piranesi. Two extremes that touch each other and paradoxically resemble each other in communicating a sense of the terribleness of human destiny. The only redemption of beauty over the crumbling world are the young bodies animated by the force of life, that of children growing up, that of young people seeking each other out and embracing each other, driven by the energy of desire.

In the 1960s Vespignani married – to Netta, who would always retain her married name, becoming a leading art dealer on the Italian scene – and became a father. His wife’s beauty, between porcelain doll and Carnaby street mannequin, hovers in the paintings of that period like a modern idol. The tender beauty of the young children forced into the torture of long poses, of which a Rai film can be seen on YouTube – Vespignani always draws from life, and even when he uses period photographs he is able to transfigure them into images truer than life itself – is immortalised in images that transform the extent of the execution time into a perfectly crafted snapshot.

Having had the opportunity to transcend the most beautiful of the drawings from the succession of Rossana Mataloni, the artist’s last companion, and having searched through auctions and private collections for a few years now for the sheets from Vespignani’s youth, Galleria del Laocoonte has been able to assemble a ‘corpus’ of around 40 drawings and five oil paintings that are among the most beautiful and representative of the Maestro’s work.

From the period between 1944-47 are some of the most beautiful – in terms of ugliness – Prostitutes of Portonaccio, Vespignani’s house bombed out, a suburban alleyway squeezed between walls animated by characters, the Port of Naples after the bombing, and a Lady with a Little Dog of poignant feebleness.

Of the oil paintings, the oldest is A quartered Ox, dated 1951, which recalls how during wartime a young Vespignani would go meditating at night, by candlelight and wrapped in wool, on Rembrandt’s work and the extremely difficult engravings, measuring himself against them already as an equal, perhaps on a copper plate, given to him by Luigi Bartolini, which at the time was almost as precious as silver.

A gloomy Suburbs, from 1965, depicts an unsettlingly large building that seems to mix the complexity of modern industrial technology with the dreamlike architecture of Piranesi’s ‘Carceri’.

Netta before the mirror, 1971, is a perfect synthesis of portrait and trompe-l’oeil painting, in which the artist’s wife seems to float fluorescently in a field of light that resembles the gold background of an antique altarpiece.

The mugshots and The Pornographer’s Archive from 1981 are part of a whole cycle of canvases entitled ‘Like Flies on Honey’, which was exhibited in a memorable exhibition at Villa Medici in 1985. They were and are formidable meditations on the ‘boys of life’ that Pasolini had immortalised on the page a quarter of a century earlier, those who were at once Pasolini’s victims and executioners. The mugshots capture their faces as if after some tragic act of bloodshed, while other photos, of young faces and young bodies seem to constitute a collage, together with clippings from pornographic magazines of the time, but are in fact a veritable tour-de-force of illusionistic painting. A Zeusi unleashed in the forbidden backroom of a newsagents.

From the Roman collection ‘Facce del Novecento’ (‘Faces of the 20th Century’), a selection of artists’ portraits that the Laocoon Gallery is in the process of cataloguing, come two true rarities: a 1947 sketch of a self-portrait that Vespignani dedicated and gave as a gift to Alfred Eisenstaed, the American photographer who had in turn portrayed him for ‘Life’ magazine, and a beautiful, well-kept paper with a portrait of the painter Muccini in bed sick. The latter, Marcello Muccini (1926-1978), made his equally brilliant debut, together with Renzo Vespignani, in the group of painters who called themselves ‘the Portonaccio gang’, angry young men who polemically exhibited their works in the streets of Via Veneto. Unfortunately, despite his initial successes, he ended up cranking out roofs of Rome – i.e. in series – for a gallery in the centre whose money he spent, for the rest of his short life, mainly on bottles of Vodka.

Other portraits are concealed in sheets of great technical virtuosity, multiplied and deformed in curved reflective surfaces, amidst neon lights and advertising lettering. It was in the 1980s when Vespignani was finally able to return to New York, composing a portrait of the city amidst the lights and pounding commercial messages of the metropolis that, conceived as a merciless critique, ends up being its glowing celebration.

Many of the sheets are in mixed media, an easy way to describe the complex way in which Vespignani drew in colour on paper, mixing lapis, coloured pencils, pastel powder applied with a brush, and many other tricks and cares that make these papers perhaps even more precious than oil canvases. These include a desperate outstretched arm with nails and the hint of a face, which looks like the detail of a crucifixion in which Christ is left hanging to rot. An eye, prodigious in truth and resemblance, such that it was chosen as the emblem of this exhibition: ‘Vespignani’s eye’, precisely, to mean that he was capable of seeing things like no-one else and – as if by magic – could make them appear on paper as he saw them.

A broken window, a Manhattan skyline, ‘fireflies’ – which are not insects, in Italian a way of saying “prostitutes” – waiting at night on the side of a road, an old ‘canara’ among abandoned buildings, a flayed greyhound running as fast as if it had run from a dog track to a circle of hell. There are many things observed from life and transfigured in the imagination of the artist, who also pays meticulous homage to idolised colleagues of the past: to Rembrandt, from whom he steals the face of the lady with a fan that once belonged to Prince Yussopov and is now in the National Gallery in London, to Van Gogh whose skull under the skin he spies in the self-portrait and impudently shows the dressing that covers his all too well known self-mutilation.