L’occhio di Vespignani

L’OCCHIO DI VESPIGNANI

A ventun anni dalla scomparsa, dopo dieci anni dall’ultima retrospettiva a lui dedicata al Casino dei Principi di Villa Torlonia, la Galleria del Laocoonte presenta L’Occhio di Vespignani, una mostra dedicata all’artista romano Renzo Vespignani (1924-2001).

VESPIGNANI’S EYE

Twenty-one years after his death and ten years after the last retrospective dedicated to him, which was held at the Casino dei Principi in Villa Torlonia, Laocoon Gallery presents Vespignani’s eye, an exhibition devoted to the Roman artist Renzo Vespignani (1924-2001).

Renzo Vespignani

Il porto di Napoli dopo il bombardamento

1946

Inchiostri colorati su carta, cm 20×32

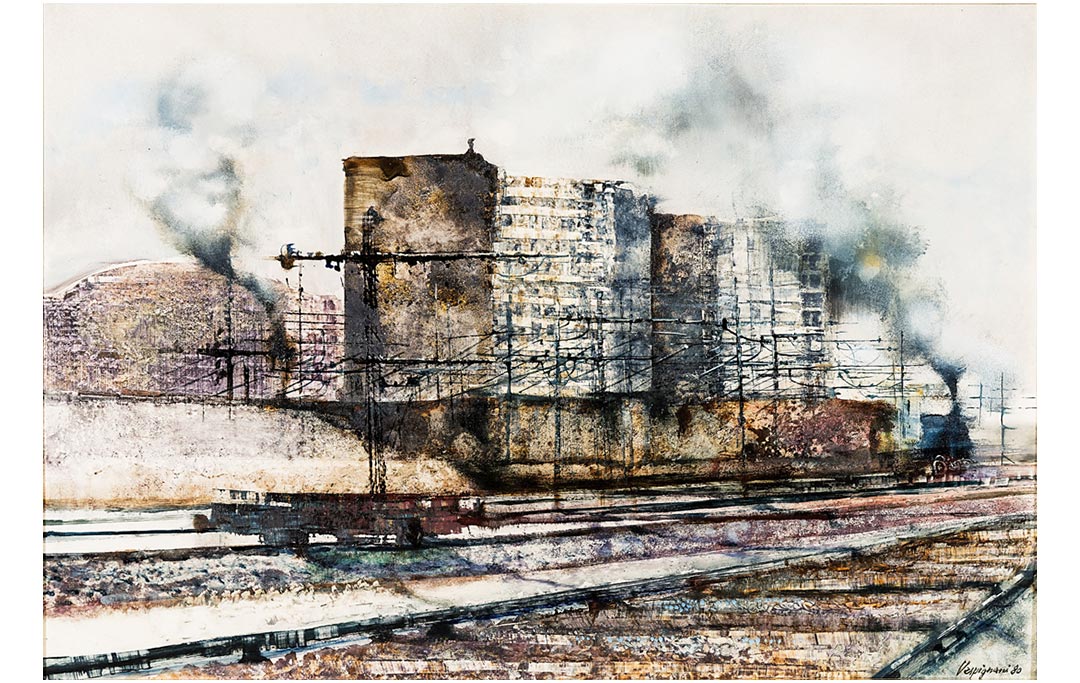

Renzo Vespignani

Periferia

1980

Tecnica mista su cartoncino, cm 35×50

Renzo Vespignani

Nudo seduto

1944

China su carta, cm 38,4×26,3

Renzo Vespignani

Manifestanti e Polizia

1957

China, acquerello e pastello su carta, cm 21×28

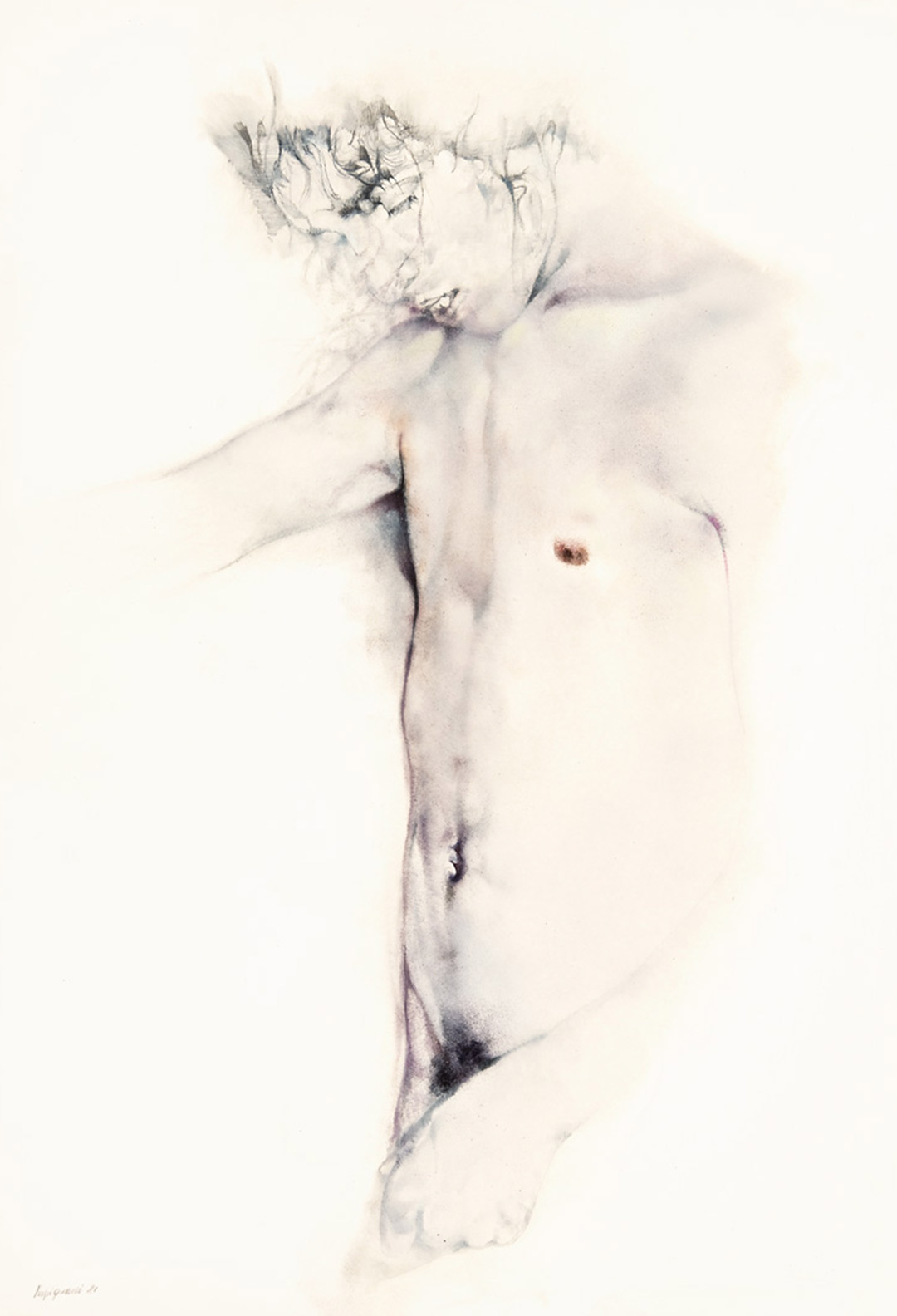

Renzo Vespignani

Nudo di ragazzo

1981

Tecnica mista su carta, cm 70,5×51,2

La mostra è stata concepita per cercare di ridare lustro alla fama un po’ appannata di colui che è stato il più dotato e straordinario disegnatore italiano del dopoguerra e uno dei più grandi incisori italiani della seconda metà del secolo scorso. Anzi, Vespignani è nato disegnatore proprio durante la guerra, i suoi primi disegni furono esposti nelle vetrine dell’auditorio dell’EIAR – la radio d’allora – per illustrare i concerti in programma, già nell’aprile del 1943. Nei mesi successivi gli avvenimenti avrebbero plasmato per sempre la personalità di un artista già completo, maturo e inimitabile a soli diciannove anni. A luglio il primo bombardamento a Roma, la caduta del fascismo subito dopo, l’armistizio e l’occupazione tedesca di Roma sono stati l’Accademia di Vespignani. Le macerie di San Lorenzo impestate dal lezzo dei cadaveri mal seppelliti sotto i crolli, quelle della sua stessa casa distrutta dal bombardamento di Portonaccio, nel marzo dell’anno seguente, sono state per il giovane artista come la foresta di Fontainebleau per i primi paesaggisti romantici francesi. La sua estetica è nata dalla contemplazione delle rovine della guerra, così come le rovine antiche hanno generato il genio di Piranesi. Il paragone non è ozioso, narra infatti un biografo contemporaneo (L. Bianconi) che il giovane Piranesi a Roma, disegnava giorno e notte, ma non Apolli e Laocoonti, bensì “i più sgangherati storpi e gobbi che vedeva il giorno per Roma… gambe impiagate, braccia rotte, e cudrioni magagnati… pezzi di carne da macello, teste di porco e di capretto”. Furono questi i primi esercizi dell’autore “Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’ Romani”, purtroppo perduti, ma chi li vide lasciò scritto che tali studi di oggetti repellenti erano però eseguiti “maravigliosamente bene”. Allo stesso modo le case distrutte, i vagoni abbandonati sui binari morti, le periferie desolate, i cadaveri tirati fuori dal cumulo dei calcinacci, i cani stroncati la cui addolorata ferocia impedisce la pietà di un colpo di grazia, le puttanone discinte di Portonaccio, rovinate come per putrefazione dall’età e dal mestiere, sono i soggetti preferiti di Vespignani, terribili, ma disegnati “maravigliosamente bene”. Tanto da sembrare raffinatissime incisioni: tratti più sottili di un capello, slavati dal pennello come in un’acquatinta, intricati e insistiti come le più profonde morsure di un’acquaforte, la maestria di Vespignani non ha paragoni, tanto più perché non mostra la lenta evoluzione di un apprendistato, ma si rivela all’improvviso, come un frutto maturo che non sia mai stato fiore. Qualche suggestione dai disegni di Franco Gentilini, più anziano di una generazione. Un vecchio libro squinternato, rubato per caso da un carrettino, con delle riproduzioni di disegni di George Grosz. Tanto bastò a Vespignani per unire lo squallore delle periferie urbane di Sironi del primo dopoguerra col più squallido orrore di un secondo dopoguerra che ancora dolorosamente faticava ad arrivare, con gli angloamericani inchiodati ad Anzio per ben cinque mesi.

Mentre Roma era ancora occupata, furono Irene Brin e Gasparo dal Corso a scoprire Vespignani, capitato per caso alla “Margherita” di via Bissolati, un negozio di cose e libri usati e qualche opera d’arte, per smerciare “a due lire” i suoi disegni. Seguirà mostra del ’45 a gennaio e replicata a giugno, sempre alla “Margherita”, e l’anno dopo all’Obelisco, la neonata galleria d’arte che la coppia Brin-dal Corso trasformeranno nella più raffinata, attiva e cosmopolita di Roma. I disegni di Vespignani vanno letteralmente a ruba, tanto che nel corso della mostra stessa vengono richiesti all’artista altri disegni per sostituire quelli venduti. Oltre agli americani, ai ricchi e vecchi e nuovi, Irene Brin rammenta anche gruppi di liceali che acquistavano un singolo disegno in società per una manata di spiccioli frutto di una sofferta colletta.

Con il fascismo l’arte ufficiale era crollata come un fondale di cartone, come certi scarponi da avanguardista di cartone pressato tinti col lucido nero che Vespignani rammentava andavano in pezzi con la prima pioggia. Dietro la scena si era rivelato un paesaggio di rovine che erano quelle che Vespignani abitava da ragazzo, dopo una primissima infanzia agiata all’Esquilino, erano quelle in cui si aggirava da sfollato, con in tasca fragili certificati medici per evitare il pericolo di un rastrellamento. Era questa Accademia del disastro italiano quella in cui il Paese seppe contemplare le proprie piaghe riuscendo a farne una poesia che doveva stupire il mondo. La “Madre romana uccisa dai tedeschi”, disegnata da Vespignani, modellata e smaltata da Leoncillo, era in realtà calabrese e si chiamava Teresa Gullace, tutto il mondo però la conosce nelle sembianze di Anna Magnani in “Roma città aperta” di Rossellini, popolana falciata da una raffica di mitra mentre corre dietro a un camion carico di rastrellati.

Vespignani è stato forse non l’unico, ma certamente il più grande interprete del neorealismo nelle arti figurative. E la notorietà internazionale venne anche per lui, immortalato in foto da Alfred Eisenstaed nel 1947 – il fotografo del famoso bacio a Times Square – compare in una pagina di Life, le sue opere vengono acquistate dal MoMA e viene invitato a tenere una mostra a New York. Per quel che riguarda il mercato americano, fu però “a flash in the pan” – un fuoco di paglia, diremmo noi – l’arrabbiata militanza comunista di Vespignani gli chiuse ben presto le porte degli Stati Uniti, disegnare Eisenhower come uno scheletro armato a passeggio con De Gasperi e Scelba al guinzaglio non fu il massimo delle referenze per ottenere un visto.

Del resto anche in tempo di pace Vespignani rimase un “pittore di rovine”, negli anni del “boom” i palazzoni delle periferie che crescono come funghi nell’Italia del benessere sono disegnati, dipinti e incisi con gli stessi segni angosciosi con cui egli aveva descritto quelli distrutti dalle bombe della guerra: tutto il suo tempo è raccontato come un unico grande cataclisma, senza soluzione di continuità tra la rovina della seconda guerra mondiale e lo sviluppo industriale, la crescita urbanistica, l’inquinamento da questi generato. La crescita del benessere per Vespignani corrisponde sempre al degrado morale e materiale del consumismo, che nei volti e nei corpi rappresentati degenera in una sorta di lebbra o decomposizione, pur sempre “maravigliosamente bene” raffigurata.

Gli incidenti stradali, con lamiere accartocciate, cristalli in frantumi e corpi riversi sull’asfalto, vengono descritti come azioni di guerra – del benessere contro l’umanità – ma riprodotti con una raffinatezza e perizia nel dettaglio, un senso del sublime nell’insieme, che fanno di Vespignani un “poeta delle rovine” moderne così come Piranesi lo è stato di quelle antiche. Entrambi sono maestri nel rappresentare il disfacimento, quello della modernità sulla natura in Vespignani, quello della natura sugli antichi monumenti in Piranesi. Due estremi che si toccano e che paradossalmente si somigliano nel comunicare un senso di terribilità del destino umano. Unico riscatto della bellezza sul mondo in disfacimento sono i giovani corpi animati dalla forza della vita, quella dei bambini che crescono, quella dei giovani che si cercano e si abbracciano spinti dall’energia del desiderio.

Negli anni ‘60 Vespignani si sposa – con Netta, che conserverà sempre il nome da sposata, divenendo gallerista e mercante d’arte di punta sulla scena italiana – e diventa padre. La bellezza della moglie, tra la bambola di porcellana e il manichino di Carnaby street, aleggia nelle pitture di quel periodo come un idolo moderno. La tenera bellezza dei figli piccoli costretti alla tortura di lunghissime pose, di cui fa fede un filmato Rai visibile su YouTube – Vespignani disegna sempre dal vero, e anche quando si serve di fotografie d’epoca è capace di trasfigurarle in immagini più vere del vero – è immortalata in immagini che trasformano la lentezza del tempo d’esecuzione in un’istantanea di perfetta fattura.

Avendo avuto la possibilità di trascegliere i più belli tra i disegni della successione di Rossana Mataloni, ultima compagna dell’artista, e andando a cercare tra aste e raccolte private da alcuni anni a questa parte, i fogli di gioventù di Vespignani, la Galleria del Laocoonte ha potuto adunare un “corpus” di circa 40 disegni e cinque olii tra i più belli e rappresentativi dell’opera del Maestro.

Del periodo tra il 1944-47 sono alcune delle più belle – per bruttezza – Prostitute di Portonaccio, La casa di Vespignani bombardata, un vicolo di periferia stretto tra muri animato di personaggi, il Porto di Napoli dopo il bombardamento, e una Signora con cagnolino di struggente pateticità.

Degli olii il più antico è un Bue squartato, del 1951, che rammenta come di notte il giovane Vespignani andava meditando in tempo di guerra, a lume di candela e infagottato di lana, l’opera e le difficilissime incisioni di Rembrandt, misurandosi con esse già alla pari, magari su una lastra di rame, regalatagli da Luigi Bartolini, che allora era preziosa quasi fosse argento.

Una fosca Periferia, del 1965, raffigura un inquietante palazzone che pare mescolare la complessità della moderna tecnologia industriale con l’architettura onirica delle “Carceri” piranesiane.

Del 1971 è invece Netta allo specchio, perfetta sintesi di ritratto e pittura à trompe-l’oeil, in cui la moglie dell’artista sembra galleggiare fluorescente in un campo di luce che pare il fondo oro di un’antica pala d’altare.

Foto segnaletiche e L’Archivio del Pornografo del 1981, fanno parte di un intero ciclo di tele intitolato “Come mosche sul miele”, che fu esposto in una memorabile mostra a Villa Medici nel 1985. Erano e sono formidabili meditazioni sui “ragazzi di vita” che Pasolini aveva immortalato su pagina un quarto di secolo prima, quelli che di Pasolini furono ad un tempo vittime e carnefici. Foto segnaletiche ne cattura il volto come dopo qualche tragico fatto di sangue, mentre altre foto, di giovani volti e di giovani corpi paiono costituire un collage, assieme a ritagli di riviste pornografiche d’epoca, ma sono in realtà un vero e proprio tour-de-force di pittura illusionistica. Uno Zeusi scatenato nel retrobottega proibito di un giornalaio.

Dalla collezione romana “Facce del Novecento”, raccolta di ritratti d’artisti di cui la Galleria del Laocoonte sta curando la catalogazione, provengono due vere rarità: uno schizzo del 1947 con un Autoritratto che Vespignani dedicò e regalò ad Alfred Eisenstaed, il fotografo americano che lo aveva ritratto a sua volta per la rivista “Life”, e una bellissima e curatissima carta con il ritratto del pittore Muccini a letto malato. Quest’ultimo, Marcello Muccini (1926-1978), esordì in maniera altrettanto brillante, assieme a Renzo Vespignani, nel gruppo di pittori che si chiamarono “la banda di Portonaccio”, giovani arrabbiati che portarono polemicamente in mostra le loro opere per strada a Via Veneto. Purtroppo, nonostante i successi iniziali, finì per fare tetti di Roma con la manovella – cioè in serie – per una galleria del centro i cui soldi spese, per il resto della sua breve vita, soprattutto in bottiglie di Vodka.

Altri ritratti sono celati in fogli di grande virtuosismo tecnico, moltiplicati e deformati in superfici riflettenti curve, tra luci al neon e scritte pubblicitarie. Sono degli anni ’80 quando Vespignani può tornare finalmente a New York, componendo tra le luci e i martellanti messaggi commerciali della metropoli un ritratto della città che, concepito come critica impietosa, finisce per esserne la rutilante celebrazione.

Molti fogli sono in tecnica mista, modo facile per descrivere la maniera complesso con cui Vespignani disegnava a colori su carta, mescolando il lapis, le matite colorate, la polvere di pastello data a pennello, e molti altri accorgimenti ed attenzioni che rendono queste carte forse più preziose delle tele ad olio. Tra queste, un disperato braccio teso con chiodi e l’accenno d’un volto, che pare il dettaglio di una crocifissione in cui il Cristo viene lasciato appeso a imputridire. Un occhio, prodigioso per verità e somiglianza, tale che si è voluto scegliere a emblema di questa mostra: “L’occhio di Vespignani”, appunto, per intendere che egli era capace di vedere le cose come nessun’altro e come per magia capace di farle apparire sulla carta così come le vedeva.

Una finestra rotta, uno skyline di Manhattan, le “lucciole” – che non sono insetti – in attesa di notte sul ciglio di una strada, una vecchia “canara” tra edifici abbandonati, un levriero scorticato che corre velocissimo come se fosse trapassato da un cinodromo ad un girone infernale. Sono tante le cose osservate dal vero e trasfigurate nell’immaginazione dall’artista, di cui non mancano anche meticolosi omaggi a idolatrati colleghi del passato: a Rembrandt, a cui ruba il volto della dama con ventaglio che fu del principe Yussopov ed ora è alla National Gallery di Londra, a Van Gogh di cui spia nell’autoritratto il teschio sotto la pelle e mostra impudicamente la medicazione che copre la sua fin troppo nota automutilazione.

The exhibition was conceived to try to restore lustre to the somewhat tarnished reputation of a man who was the most gifted and extraordinary post-war Italian draughtsman and one of the greatest Italian engravers of the second half of the last century. Indeed, Vespignani became a draughtsman during the war, when his first drawings were displayed in the windows of the EIAR auditorium – the radio station of the time – to illustrate scheduled concerts as early as April 1943. In the following months, events would forever shape the personality of an artist who was already complete, mature and inimitable at only nineteen years of age. In July, the first bombing of Rome, immediately followed by the fall of Fascism, the armistice and the German occupation of Rome were Vespignani’s academy. The remains of San Lorenzo, impregnated with the stench of badly buried corpses amongst the rubble, his own house destroyed by the bombing of Portonaccio in March of the following year, were for the young artist like the forest of Fontainebleau for the first French Romantic landscape painters. His aesthetic was born from contemplation of the ruins of war, just as ancient ruins generated Piranesi’s genius. The comparison is not idle, as a contemporary biographer (L. Bianconi) recounts that the young Piranesi in Rome, drew day and night, but not Apollo and Laocoon, but ‘the most ramshackle cripples and hunchbacks that he saw during the day in Rome… legs stuck, arms broken, and skinny cudrioni… pieces of butcher’s meat, heads of swine and kid’. These were the author’s first exercises ‘Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’ Romani’, unfortunately lost, but those who saw them left written that such studies of repulsive objects were nevertheless executed ‘maravigliosamente bene’, marvellously well. In the same way, the destroyed houses, the abandoned wagons on the dead tracks, the desolate suburbs, the corpses pulled from heaps of rubble, the mangled dogs whose grieved ferocity prevents the mercy of a coup de grace, the discarded whores of Portonaccio, ruined as if by putrefaction by their age and trade, are Vespignani’s favourite subjects, terrible, but drawn ‘marvellously well’. So much so that they seem to be refined engravings: strokes finer than a hair, washed out by the brush as in an aquatint, intricate and insistent like the deepest bites of an etching, Vespignani’s mastery is unparalleled, especially because it does not show the slow evolution of an apprenticeship, but reveals itself suddenly, like a ripe fruit that has never been a flower: a few suggestions from the drawings of Franco Gentilini, a generation older; a shabby old book, stolen by chance from a cart, with reproductions of drawings by George Grosz. This was enough for Vespignani to unite the squalor of Sironi’s urban suburbs after the First World War with the bleakest horror of a Second World War that was still painfully struggling to arrive, with the Anglo-Americans pinned down at Anzio for a good five months.

While Rome was still occupied, it was Irene Brin and Gasparo dal Corso who discovered Vespignani, who happened by chance to be at the “Margherita” in Via Bissolati, a shop selling used books and a few works of art, to sell his drawings “for two lire”. This was followed by an exhibition in January of 1945 that was replicated in June, again at the “Margherita”, and the following year at the Obelisco, then a newly-established art gallery that the Brin-Dal Corso couple would transform into the most refined, active and cosmopolitan in Rome. Vespignani’s drawings literally sell like hot cakes, so much so that during the course of the exhibition itself, the artist is asked for more drawings to replace those sold. In addition to the Americans, of both old and new money, Irene Brin also recalls groups of high school students who would buy a single drawing in society for a handful of pennies from a hard-earned collection.

With Fascism, official art had collapsed like a house of cards, like certain avant-garde boots made of from pressed cardboard and dyed with black polish that Vespignani recalled ravaged by the first rain. Behind the scene was revealed a landscape of ruins that were those inhabited by Vespignani as a boy, following an affluent early childhood at the Esquiline, here he wandered as an evacuee, with fragile medical certificates in his pockets to avoid the danger of a round-up. It was this Academy of Italian Disaster in which the country was able to contemplate its own wounds and turn them into a poem that would amaze the world. The ‘Roman Mother killed by the Germans’, drawn by Vespignani, modelled and enamelled by Leoncillo, was actually from Calabria and was called Teresa Gullace, but the whole world knows her in the guise of Anna Magnani in Rossellini’s ‘Roma città aperta’, a commoner mowed down by a machine-gun fire while running behind a truck loaded with round-ups.

Vespignani was perhaps not the only one, but certainly the greatest interpreter of neo-realism in the figurative arts, and international fame also came for him, immortalised in pictures by Alfred Eisenstaed in 1947 – the photographer of the famous kiss in Times Square – he appeared on a page of Life after his works were bought by MoMA and he was invited to hold an exhibition in New York. As far as the American market was concerned, however, it was somewhat of ‘a flash in the pan’ – with Vespignani’s angry communist militancy soon closing the doors that had opened so genially, drawing Eisenhower as an armed skeleton strolling with De Gasperi and Scelba on a leash was not the best of references for obtaining a visa.

After all, even in peacetime Vespignani remained a ‘painter of ruins’; in the ‘boom’ years, the suburban blocks of flats growing like mushrooms in Italy’s affluence are drawn, painted and engraved with the same anguished signs with which he had described those destroyed by the bombs of the war: his whole time is recounted as one great cataclysm, with no solution of continuity between the ruin of the Second World War and the industrial development, urban growth and pollution they generated. The growth of prosperity for Vespignani always corresponds to the moral and material degradation of consumerism, which in the faces and bodies depicted degenerates into a sort of leprosy or decomposition, though always ‘marvellously well’ depicted.

The road accidents, with crumpled metal sheets, shattered glass and bodies lying on the asphalt, are described as acts of war – of wealth against humanity – but reproduced with a refinement and expertise in detail, a sense of the sublime in the whole, that make Vespignani a modern ‘poet of ruins’ just as Piranesi was of ancient ones. Both are masters in representing decay, that of modernity on nature in Vespignani, that of nature on ancient monuments in Piranesi. Two extremes that touch each other and paradoxically resemble each other in communicating a sense of the terribleness of human destiny. The only redemption of beauty over the crumbling world are the young bodies animated by the force of life, that of children growing up, that of young people seeking each other out and embracing each other, driven by the energy of desire.

In the 1960s Vespignani married – to Netta, who would always retain her married name, becoming a leading art dealer on the Italian scene – and became a father. His wife’s beauty, between porcelain doll and Carnaby street mannequin, hovers in the paintings of that period like a modern idol. The tender beauty of the young children forced into the torture of long poses, of which a Rai film can be seen on YouTube – Vespignani always draws from life, and even when he uses period photographs he is able to transfigure them into images truer than life itself – is immortalised in images that transform the extent of the execution time into a perfectly crafted snapshot.

Having had the opportunity to transcend the most beautiful of the drawings from the succession of Rossana Mataloni, the artist’s last companion, and having searched through auctions and private collections for a few years now for the sheets from Vespignani’s youth, Galleria del Laocoonte has been able to assemble a ‘corpus’ of around 40 drawings and five oil paintings that are among the most beautiful and representative of the Maestro’s work.

From the period between 1944-47 are some of the most beautiful – in terms of ugliness – Prostitutes of Portonaccio, Vespignani’s house bombed out, a suburban alleyway squeezed between walls animated by characters, the Port of Naples after the bombing, and a Lady with a Little Dog of poignant feebleness.

Of the oil paintings, the oldest is A quartered Ox, dated 1951, which recalls how during wartime a young Vespignani would go meditating at night, by candlelight and wrapped in wool, on Rembrandt’s work and the extremely difficult engravings, measuring himself against them already as an equal, perhaps on a copper plate, given to him by Luigi Bartolini, which at the time was almost as precious as silver.

A gloomy Suburbs, from 1965, depicts an unsettlingly large building that seems to mix the complexity of modern industrial technology with the dreamlike architecture of Piranesi’s ‘Carceri’.

Netta before the mirror, 1971, is a perfect synthesis of portrait and trompe-l’oeil painting, in which the artist’s wife seems to float fluorescently in a field of light that resembles the gold background of an antique altarpiece.

The mugshots and The Pornographer’s Archive from 1981 are part of a whole cycle of canvases entitled ‘Like Flies on Honey’, which was exhibited in a memorable exhibition at Villa Medici in 1985. They were and are formidable meditations on the ‘boys of life’ that Pasolini had immortalised on the page a quarter of a century earlier, those who were at once Pasolini’s victims and executioners. The mugshots capture their faces as if after some tragic act of bloodshed, while other photos, of young faces and young bodies seem to constitute a collage, together with clippings from pornographic magazines of the time, but are in fact a veritable tour-de-force of illusionistic painting. A Zeusi unleashed in the forbidden backroom of a newsagents.

From the Roman collection ‘Facce del Novecento’ (‘Faces of the 20th Century’), a selection of artists’ portraits that the Laocoon Gallery is in the process of cataloguing, come two true rarities: a 1947 sketch of a self-portrait that Vespignani dedicated and gave as a gift to Alfred Eisenstaed, the American photographer who had in turn portrayed him for ‘Life’ magazine, and a beautiful, well-kept paper with a portrait of the painter Muccini in bed sick. The latter, Marcello Muccini (1926-1978), made his equally brilliant debut, together with Renzo Vespignani, in the group of painters who called themselves ‘the Portonaccio gang’, angry young men who polemically exhibited their works in the streets of Via Veneto. Unfortunately, despite his initial successes, he ended up cranking out roofs of Rome – i.e. in series – for a gallery in the centre whose money he spent, for the rest of his short life, mainly on bottles of Vodka.

Other portraits are concealed in sheets of great technical virtuosity, multiplied and deformed in curved reflective surfaces, amidst neon lights and advertising lettering. It was in the 1980s when Vespignani was finally able to return to New York, composing a portrait of the city amidst the lights and pounding commercial messages of the metropolis that, conceived as a merciless critique, ends up being its glowing celebration.

Many of the sheets are in mixed media, an easy way to describe the complex way in which Vespignani drew in colour on paper, mixing lapis, coloured pencils, pastel powder applied with a brush, and many other tricks and cares that make these papers perhaps even more precious than oil canvases. These include a desperate outstretched arm with nails and the hint of a face, which looks like the detail of a crucifixion in which Christ is left hanging to rot. An eye, prodigious in truth and resemblance, such that it was chosen as the emblem of this exhibition: ‘Vespignani’s eye’, precisely, to mean that he was capable of seeing things like no-one else and – as if by magic – could make them appear on paper as he saw them.

A broken window, a Manhattan skyline, ‘fireflies’ – which are not insects, in Italian a way of saying “prostitutes” – waiting at night on the side of a road, an old ‘canara’ among abandoned buildings, a flayed greyhound running as fast as if it had run from a dog track to a circle of hell. There are many things observed from life and transfigured in the imagination of the artist, who also pays meticulous homage to idolised colleagues of the past: to Rembrandt, from whom he steals the face of the lady with a fan that once belonged to Prince Yussopov and is now in the National Gallery in London, to Van Gogh whose skull under the skin he spies in the self-portrait and impudently shows the dressing that covers his all too well known self-mutilation.