Gino Severini And The Mosaics Of ‘The Third Rome’

Gino Severini And The Mosaics Of ‘The Third Rome’

There are few locations in Italy’s capital that give a better insight into the architectural style adopted during this epoch than the famous Foro Italico sports complex, originally constructed as part of a bid to hold the ill-fated 1940 Olympic Games, and Palazzo degli Uffici, the imposing inaugural building of the new district of EUR, which was created in the build up to the eventually cancelled 1942 World Fair.

Gino Severini, as a highly revered painter and leading member of the Futurist movement, was commissioned to design scenes which were used in a number of important mosaics executed during this period.

The largest of these mosaics is a walkway covering in excess of 7,000 square metres and containing more than 50 million polychromic tesserae of the same marble used by the ancient Romans. The avenue, which leads to a 300 tonne Carrara marble obelisk, is named Viale del Monolite, and depicts figurative motifs intended to represent both the history of Rome and fascist life.

Severini’s production for this assemblage contains a disaggregated group of symbolic figures, at the centre of which is a male heroic nude leaning against a littoral beam, surrounded by the symbols of the arts and sciences as well as by those of strength (the lion), the empire (the eagle), and Rome (the wolf). The male figure, also interpreted by historians as Romulus or Augustus, almost certainly represents Fascism or The Empire. It is a composition ideally inscribed in a circle, whose figures are spread as in ancient rosettes; with the usual discretion the Fasces, which characterises the male figure, camouflages itself with the folds of his mantle, while particular attention has been paid to the details and attributes of the symbolic figures surrounding the central character. Severini clearly tries to escape the rhetoric of the theme by proposing a decoration in which the rhythmic alternation of black and white scores works, and classicism is repurposed between Cubist allusions, like a world once dreamed and now lost.

A large scale second drawing by Severini refers to a mosaic executed at the Duce gym of the same complex under the direction of architect Luigi Moretti. The environment, conceived by perhaps the most original architect of his generation, is a classical room with elongated proportions that are completely covered in marble. Severini’s mosaics, featuring black figures on a white background, distributed in different places on the floor and walls, counterpoint this rarefied space (in which apparently the Duce never went) without affecting the space conceived by the architect. At the entrance there is a kind of ‘carpet’ with the symbolic figure of fascist Italy juxtaposed with a fallen Icarus and topped by a roaring Lion, the symbol of Mussolini’s zodiac sign; it is a discreet introibo, evocative of the Renaissance virtues of the new Prince, to the superb epiphany of the Morettian chamber, cadenzad by just three plastic elements, a spiral staircase ascending through the hall and two beautiful golden sculptures from Silvio Canevari (The Archer, The Fromboliere). At the bottom on the left, behind a marble septum, a Cubist still life on the ground introduces the elongated wall of the dressing room, upon which the rest of the athletes and the theme of the hunt are described; the remaining figure of the archer can be seen from the entrance behind the bronzes of Canevari. Severini’s composition is characterized by the paratactic rhythm with which the figures appear and loom on the wall. There is no narrative bond that unites them. From the two male nudes on the left, playing with birds, to the isolated figure of the hunter, arched on the ground, and the prey surrounded by pigeons and roosters. At the top a flock of birds wheel and circle and, out of symmetry, one of the artist’s characteristic still lifes. Finally, a pencil stroke behind the athletes on the left reveals the suggestion that the author had once placed a leafy tree in the background, later removing it.

The mosaic panel for which Severini, along with his contemporaries, provided detailed drawings intended to guide the mosaicists in charge of the works at the monumental fountain at the entrance of Palazzo degli Uffici give further insight into the brilliance of the artist. Like many other public works, the history of this assignment was thwarted. It was a commission that the artist considered minor at the time, having hoped to receive that of the decoration of the Salone di Libera for Palazzo dei Congressi. This assignment would have provided much higher prestige and visibility but was ultimately prohibited by his appointment as commissioner in the jury of the competition. The fountain, whose design history has been dutifully reconstructed by A. Greco [E42 : utopia e scenario del regime…,cit., pp. 310-314], was conceived by the architect Gaetano Minnucci and consists of three basins in sequence. The sides were designed by Giulio Rosso and Giovanni Guerrini, while for the central basin Severini conceived six panels inspired by the glorification of the origins of the Lazio region and Rome. The style relates intimately to his experience with the recently completed mosaics for the Foro Italico; it is a polite reinterpretation of Roman and Pompeian motifs that is more inclined to confront the bucolic themes of the Virgilian lyric than the triumphalist subject matter preferred by the regime.

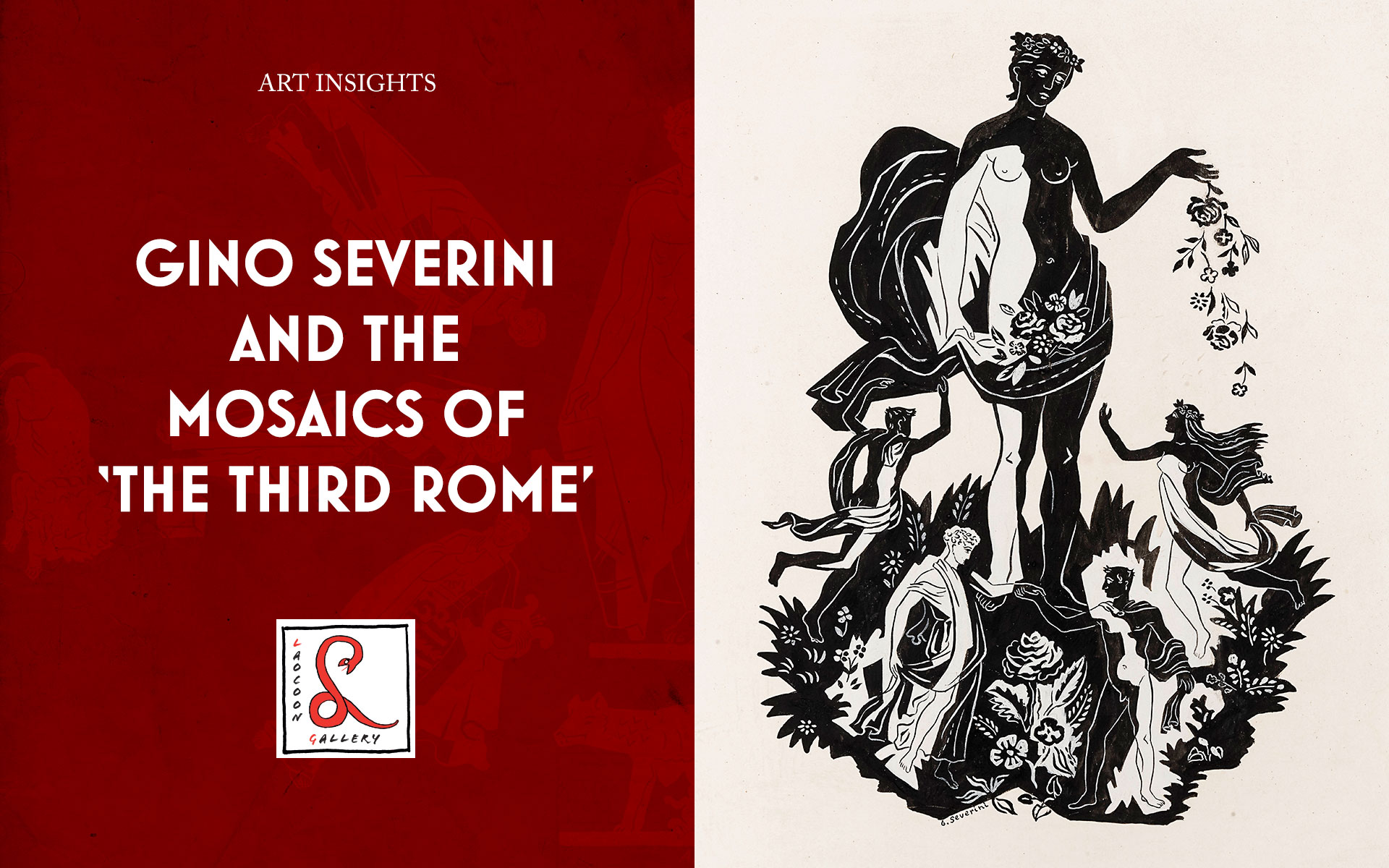

For the panel of Romulus, who governs on a prosperous forest surrounded by six horses (which in the final creation became eight) the artist performed two different versions, essentially very similar, one more naturalistic, the other – as shown here – a more geometric form, which was ultimately discarded. The geometrical cuts in white of the black fields and figures are of clear Cubist memory, and they give a lively rhythm to the composition, removing it from the illustrative anecdote.

The presence in the archive of Romana Severini of several dictionaries of ancient mythology, belonging to the artist and bearing many annotations by his own hand, explains the accuracy with which the artist intended to respond to the requests of his client. It is likely that the iconographic indications were quite generic. The artist, however, determined to build an iconographic tale allusive to the celebration of The Third Rome and its rebirth under the new emperor that transferred, via the technique of mosaic, forms taken from the Roman decorative repertoire as long ago as the early imperial age and beyond. Furthermore, there is an interesting turning point in these works in comparison to the compositional modules experimented with in the great secular compositions of the second half of the 1930s. The encounter with classical iconography induces Severini to abandon those highly geometric pyramidal constructions as seen in his panels for the exhibition of Dopolavoro in 1938, or of Neo-Byzantine taste like those in the mosaics of the Palace of Justice in Milan, for a much more fluid composition, free and rich in imagination and allowing him to give space to many decorative details which were previously sacrificed.

The figure of Flora, allusive to the richness and fruitfulness guaranteed by new times, demonstrates this perfectly. Instead of standing isolated at the bottom, she is clung to by a group of minor figures who are of pure invention, but in which it is even possible to trace some motifs already present in the Cubist era.

The third drawing depicts an ancient Roman deity who presided over the wilds, akin to Faunus. Silvano was considered the god of the woods and the countryside, protector of flocks and property. Severini depicts him according to the Roman iconography, sickle in hand and dog beside him, surrounded by an abundant harvest of fruits. The panel is, in the arrangement designed for the fountain, the counterpart of Flora; with one placed on either side of the central scene which faces the palace, where Time, or Saturn, is shown, a male figure winged with scythe and hourglass, placed in the middle of the four seasons. As is the case with Flora, the author takes advantage of the countryside theme to set up, largely at the feet of the male nude, a still life full of details and hunting trophies that directly refer to his long pictorial exercise of the fourth decade, in which classically inspired still lifes – sometimes associated with masks and ancient female statues – predominated over any other subject. These bucolic and pastoral motifs were evidently very welcome in the society of the time, as displayed by Gio Ponti in Paris, in 1937, with his adornment of a dining room for the International Exhibition of Decorative Art, and later, in 1940, in the panels executed for Villa Innocenti in Frascati, with its figures of Pomona and Vertunno very close to the mosaics of the EUR.

Of all the figurations performed for the fountain, the panels of Flora and Silvano certainly appear to be the happiest and the least constricted by the need to adhere, albeit in Gino Severini’s trademark sober manner, to the celebratory spirit that animated the entire conception of the work conceived by the architect Minnucci. Although the letters preserved in the archives record the artist’s substantial dissatisfaction with the limited scope of the assignment, he certainly did not object to the revival, in a contemporary key, of the ancient technique of bichrome mosaic. A method that presented an abundance of conceptual affinities with the graphic synthesis elaborated by Cubism.